Imagine a trial in 1776, so well-attended it was one of the hottest tickets in London, where the judges were over 100 members of the House of Lords. The woman being judged is the wife of the Earl of Bristol and the widow of the Duke of Kingston, known to history as the notorious, infamous, etc. so-called Duchess of Kingston, Elizabeth Chudleigh. She is accused of marrying the Duke while her first husband was still living. The penalty for bigamy is death.

A brief Web search for this lady's story will reveal all the details, and the various accounts are worth reading, for it's quite an extraordinary tale. What I have cobbled together here is an amalgam of several sources, and of course they don't all agree. For those wanting something more substantial and reliable, the most recent comprehensive work I am aware of is this book:

Elizabeth: The Scandalous Life of an Eighteenth Century Duchess, by Claire Gervat (2004, Arrow Books).

I rush to say I haven't read the book but in the course of doing the research for this article, I became so interested in the Duchess that I have just this minute purchased the book and will enjoy reading it as I sip iced tea and eat bonbons on the chaise longue. It was favourably reviewed in the UK paper The Telegraph, with Frances Wilson, the reviewer, commenting that the research is solid.

From the various accounts I have read, and in trying to put more weight on the first-hand and contemporary sources, I have got my own idea of the story, which goes like this.

Elizabeth Chudleigh was almost a simple country lass from a good family. Her widowed mother struggled to survive and to keep up appearances in London society. Fortunately, Elizabeth's good looks and wit got her a place as a Maid of Honour to Augusta, Princess of Wales.

Young Elizabeth, disappointed in love by the Duke of Hamilton and cajoled by a deceptive aunt to marry the second man in line to become the the Earl of Bristol, impulsively and secretly did marry him, Augustus John Hervey by name. They had very little time together, as he was off with the navy right away, but their union produced two things: a conviction in both that they were not all that good together, and a son, who died in infancy. The other thing this marriage produced was evidence: a marriage register, witnesses to the wedding, and a doctor who delivered the baby.

The marriage was secret from the start because a married woman could not be a Maid of Honour, and Elizabeth wanted to keep both the status and the income from the position. It would seem, at least at times in her life, and to certain observers, that she never really accepted the fact of her marriage. It was much more convenient to be a socialite and a climber as a single woman. However, she used the marriage when it suited her, and forgot it, even denied it, whenever it didn't fit her current scheme.

Read that Telegraph review if you want a colourful description of how Elizabeth was at once fascinating and vulgar.

One of her famous stunts was her appearance at a costume party, where King George II, among others, was present, and in fact the good King took quite a personal interest in Miss Chudleigh's original costume. She was semi-dressed as a maiden from Greek mythology, Iphigenia. Whether it was historical faithfulness or mere artistic license at work, readers will have to decide for themselves, but the costume Miss Chudleigh / Mrs. Hervey wore apparently began at the waist and worked its way diaphanously down her legs, declining to travel any distance at all in the northerly direction. Topless, in other words.

Another time she apparently brandished a pistol to make her point in an argument.

Who knows what exactly Elizabeth's amorous history was, but it does seem to have been the best of 18th century tabloid fodder.

Interestingly, Evelyn Medows was cut from not radically dissimilar cloth. Despite the fact that they were opponents in the notorious bigamy trial, and had a longstanding dispute over her inheritance, I think they each recognized in the other a bit of themselves.

The story will continue in another post.

The intriguing life of Mr. Evelyn Medows, late of 51 Charles Street, Berkeley Square, London

A timeline and links for Harriet Maria Campbell, formerly Dickson, formerly Medows, nee Norie

Sir John Campbell's brother-in-law wrote the leading work on navigation: J.W. Norie

From the Royal kalendar, 1820, an interesting charity name

How could Sir John Campbell, K.C.T.S., afford to live on Charles Street, Berkeley Square?

Odds and ends that turn up in the course of doing family history and genealogy research. Every name has a story. At least one.

Showing posts with label uk. Show all posts

Showing posts with label uk. Show all posts

Monday, August 29, 2011

Monday, June 20, 2011

Why you should keep on digging when researching family history

I had the birth, marriage, and death information for Sir John Campbell, KCTS some time ago. Why keep going?

There are a few reasons, but here is one of them: to learn what kind of man he was.

I've made inferences, which is really all I can do, given the lack of direct evidence about the man. However, there are a few eyewitnesses who described him as a soldier (Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, commended him in his reports of battles in Portugal), as a prisoner of war in Portugal, and even in the House of Lords, he was a topic of conversation, albeit perhaps as more of a political football than as an individual.

None of this shed light on his home life, which is what I hoped to find out about as I continued the research.

Through a lot of persistent searching for anything about him, I thought I had found pretty much all I could in terms of books or articles mentioning him specifically, to the extent that these appear online. That will change with time, and there's a lesson: go back in a year, and then in another year, and another, until you are satisfied. More information becomes available all the time. Never close the door.

I also learned the value of tracking relatives beyond the immediate family. Well, "learned" isn't really the right word. "Proved" might be closer.

The best nugget came from searching his name in conjunction with the name of a house, Hunsdon House. How did I know to do that search? Because I traced Sir John's daughter, Elizabeth, his only surviving child. She married into the Calvert family, and lived for a time at their property, Hunsdon House.

Pushing further into the Calverts revealed two interesting sources: the published memoirs of Elizabeth's mother-in-law, Lady Frances Calvert (nee Pery), and the fact that one of Elizabeth's nephews became a very well-known public figure. He was Edmond Warre (1837 to 1920) who is remembered as a famous oarsman for Oxford and a long-time master and then Headmaster (1880 to 1909) of Eton College.

In Edmond Warre, D.D., C.B., C.V.O.: Sometime Headmaster and Provost of Eton College, by Charles Robert Leslie Fletcher (J. Murray, 1922), the Google Books copy, I found this passage.

"… Sir John Campbell (a Peninsular veteran who had married a Portuguese lady); he was not such a favourite with the children as Uncle Felix".

Because I don't have the actual book, just snippets, I can't easily see the whole page. I'm working on digging up interesting bits from the book for my next post.

There are a few reasons, but here is one of them: to learn what kind of man he was.

I've made inferences, which is really all I can do, given the lack of direct evidence about the man. However, there are a few eyewitnesses who described him as a soldier (Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, commended him in his reports of battles in Portugal), as a prisoner of war in Portugal, and even in the House of Lords, he was a topic of conversation, albeit perhaps as more of a political football than as an individual.

None of this shed light on his home life, which is what I hoped to find out about as I continued the research.

Through a lot of persistent searching for anything about him, I thought I had found pretty much all I could in terms of books or articles mentioning him specifically, to the extent that these appear online. That will change with time, and there's a lesson: go back in a year, and then in another year, and another, until you are satisfied. More information becomes available all the time. Never close the door.

I also learned the value of tracking relatives beyond the immediate family. Well, "learned" isn't really the right word. "Proved" might be closer.

The best nugget came from searching his name in conjunction with the name of a house, Hunsdon House. How did I know to do that search? Because I traced Sir John's daughter, Elizabeth, his only surviving child. She married into the Calvert family, and lived for a time at their property, Hunsdon House.

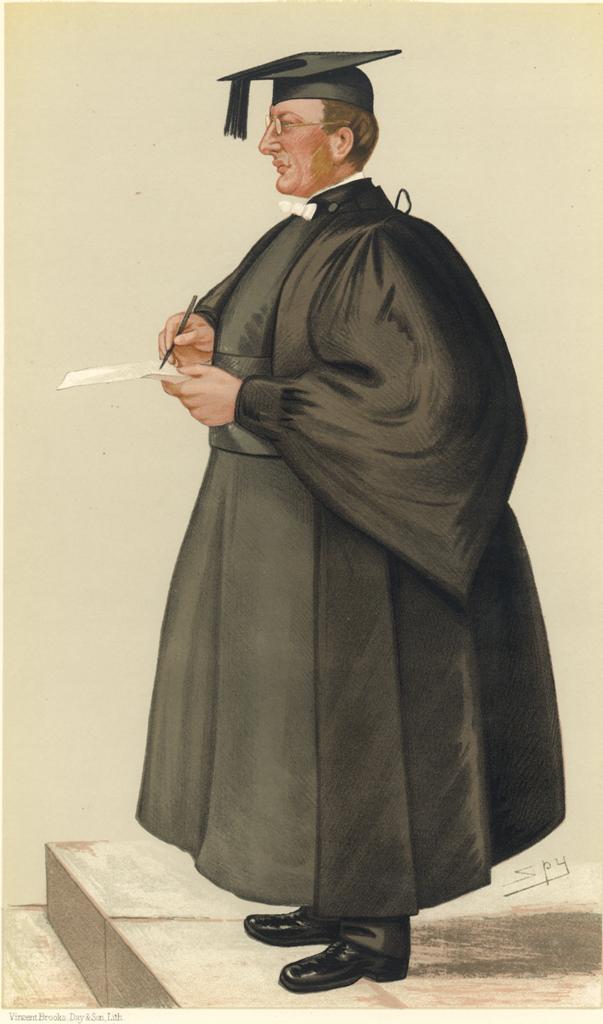

Pushing further into the Calverts revealed two interesting sources: the published memoirs of Elizabeth's mother-in-law, Lady Frances Calvert (nee Pery), and the fact that one of Elizabeth's nephews became a very well-known public figure. He was Edmond Warre (1837 to 1920) who is remembered as a famous oarsman for Oxford and a long-time master and then Headmaster (1880 to 1909) of Eton College.

| |

| Edmond Warre, "The Head". In Vanity Fair magazine, June 20, 1885. |

"… Sir John Campbell (a Peninsular veteran who had married a Portuguese lady); he was not such a favourite with the children as Uncle Felix".

Because I don't have the actual book, just snippets, I can't easily see the whole page. I'm working on digging up interesting bits from the book for my next post.

Labels:

edmond warre,

england,

eton college,

family history,

genealogy,

hertfordshire,

hundson,

sir john campbell,

uk

Thursday, June 2, 2011

Summoned by loyalty, a soldier returns to the field, but for the wrong side

In 1824, Sir John Campbell found himself, at the age of 44, a widower with a 6-year-old daughter, and in mourning for his 3-year-old son. Before the year was out, he had resigned from the army, where he had distinguished himself in fighting in Portugal during the Peninsular Wars of the early 19th century. He and young Elizabeth were apparently living quietly in London. Then everything changed, again.

Sir John's late wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, was Portuguese and I suspect from a good family. Sir John himself was friends with the royal family, or at least, part of it. By the late 1820s, Portugal was in a crisis over succession, which was a fight between one brother (Dom Pedro) favouring a constitutional monarchy and reform, and the other (Dom Miguel) wanting to stay with an absolute monarchy. It turned into a civil war.

The story of the Portuguese War of the Two Brothers is complicated. The highlights, for my purposes are simple enough, though.

British soldiers fought on both sides! Their leaders were officers who had been brothers in arms in the earlier Peninsular Wars. Men on both sides held knighthoods in both England and Portugal. All of them were at least notionally fighting illegally, according to the Foreign Enlistment Act.

To make things a little awkward for me in the research department, there were too many Campbells around, officers with the KCTS decoration, who served in the Peninsular Wars and possibly in this Portuguese civil war. Anyone who decides to study the story more closely will need to be cautious. I can only hope I am not getting the facts too confused.

There is no doubt that Sir John Campbell of my story, the man who eventually lives at 51 Charles Street, was at the head of the Miguelite forces, as they were called. He supported the absolutist cause whole-heartedly. On the other side were Admiral Sartorius and then Sir Charles Napier. Their respective forces were a mixture of English and Portuguese, and not professional soldiers, but what we might charitably call a motley crew.

A few brief glances at some of the debates in the House of Lords and the Commons after the war ended indicates that the British politicians were not in unanimous support of either side in the Portuguese war. Again, this is an over-simplification, but Sir John became something of a political football.

In the early days of the war, his side did well, but then the tide turned. Sir John was captured on board a ship (apparently leaving Portugal) with some allegedly incriminating papers. Papers or no, his side had lost. He became a prisoner of war.

This was an unpleasant imprisonment. Reading between the lines, I suspect there was a good deal of seeking revenge involved, because in some quarters the Miguelites had a reputation for being barbaric to their own prisioners. English visitors to Portugal after the war, in the early 1830s, reported seeing Sir John behind the bars of the prison compound.

His appeals to the English government for help went unanswered, on the basis that he was fighting in a foreign war on foreign soil, not in a British cause.

Why did he do it?

I've read that Sir John was a personal friend of Dom Miguel from his earlier time in Portugal, and I assume that the granting of the honour of KCTS, whenever that was, cemented that friendship. Sir John's politics must have been conservative, which mattered a great deal against the backdrop of the Reform movement in England.

He was held for at least nine months, much of which was apparently in solitary confinement. The degree of deprivation is in the eye of the beholder, but certainly it was a hard time, during which he was abandoned by his country.

I'm a little surprised that he was ever allowed to return to England. Having fought for the losing side in a battle that put British soldiers against each other, he could have been called treasonous without a huge stretch of the imagination.

I suspect what saved him was the fact that no one had clean hands.

By the time he returned to England in about 1834, his daughter was 16. He had been away from her for a few years (at least).

Here was a man who had spent much of his life achieving honour and glory as a soldier, only to end up disgraced. In the Commons debates, reference was made to his having a Portuguese wife (with the implication being that his loyalty wasn't to Britain), but no one pointed out that Maria Brigida had been dead for ten years.

He'd lost his wife and son, had hardly seen his daughter, had fought on a losing side and been imprisoned, and could probably never return to the country he must have come to love, Portugal.

He had reason to be a bitter and disappointed man, and maybe he was. Or, maybe he was so convinced of the rightness of his cause that he spent the rest of his life deploring the wrongs done to him. I don't know. The dictionary of biography says he lived a quiet life.

The quiet lasted until 1863, some 20 years after the civil war ended. It was then succeeded by that quiet which comes to us all, one day.

The first book, by Shaw, is about the War of Two Brothers. The other two books are from the Duke of Wellington's earlier experiences in Portugal. I have written before that Sir John Campbell was mentioned favourably in dispatches by Wellesley, late the Duke, but this may not be true, or it may be true but some of the mentions may refer to other Campbells. I post links to some of the books here in case anyone is interested in finding out more.

Sir John's late wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, was Portuguese and I suspect from a good family. Sir John himself was friends with the royal family, or at least, part of it. By the late 1820s, Portugal was in a crisis over succession, which was a fight between one brother (Dom Pedro) favouring a constitutional monarchy and reform, and the other (Dom Miguel) wanting to stay with an absolute monarchy. It turned into a civil war.

British soldiers fought on both sides! Their leaders were officers who had been brothers in arms in the earlier Peninsular Wars. Men on both sides held knighthoods in both England and Portugal. All of them were at least notionally fighting illegally, according to the Foreign Enlistment Act.

To make things a little awkward for me in the research department, there were too many Campbells around, officers with the KCTS decoration, who served in the Peninsular Wars and possibly in this Portuguese civil war. Anyone who decides to study the story more closely will need to be cautious. I can only hope I am not getting the facts too confused.

There is no doubt that Sir John Campbell of my story, the man who eventually lives at 51 Charles Street, was at the head of the Miguelite forces, as they were called. He supported the absolutist cause whole-heartedly. On the other side were Admiral Sartorius and then Sir Charles Napier. Their respective forces were a mixture of English and Portuguese, and not professional soldiers, but what we might charitably call a motley crew.

A few brief glances at some of the debates in the House of Lords and the Commons after the war ended indicates that the British politicians were not in unanimous support of either side in the Portuguese war. Again, this is an over-simplification, but Sir John became something of a political football.

In the early days of the war, his side did well, but then the tide turned. Sir John was captured on board a ship (apparently leaving Portugal) with some allegedly incriminating papers. Papers or no, his side had lost. He became a prisoner of war.

This was an unpleasant imprisonment. Reading between the lines, I suspect there was a good deal of seeking revenge involved, because in some quarters the Miguelites had a reputation for being barbaric to their own prisioners. English visitors to Portugal after the war, in the early 1830s, reported seeing Sir John behind the bars of the prison compound.

His appeals to the English government for help went unanswered, on the basis that he was fighting in a foreign war on foreign soil, not in a British cause.

Why did he do it?

I've read that Sir John was a personal friend of Dom Miguel from his earlier time in Portugal, and I assume that the granting of the honour of KCTS, whenever that was, cemented that friendship. Sir John's politics must have been conservative, which mattered a great deal against the backdrop of the Reform movement in England.

He was held for at least nine months, much of which was apparently in solitary confinement. The degree of deprivation is in the eye of the beholder, but certainly it was a hard time, during which he was abandoned by his country.

I'm a little surprised that he was ever allowed to return to England. Having fought for the losing side in a battle that put British soldiers against each other, he could have been called treasonous without a huge stretch of the imagination.

I suspect what saved him was the fact that no one had clean hands.

By the time he returned to England in about 1834, his daughter was 16. He had been away from her for a few years (at least).

Here was a man who had spent much of his life achieving honour and glory as a soldier, only to end up disgraced. In the Commons debates, reference was made to his having a Portuguese wife (with the implication being that his loyalty wasn't to Britain), but no one pointed out that Maria Brigida had been dead for ten years.

He'd lost his wife and son, had hardly seen his daughter, had fought on a losing side and been imprisoned, and could probably never return to the country he must have come to love, Portugal.

He had reason to be a bitter and disappointed man, and maybe he was. Or, maybe he was so convinced of the rightness of his cause that he spent the rest of his life deploring the wrongs done to him. I don't know. The dictionary of biography says he lived a quiet life.

The quiet lasted until 1863, some 20 years after the civil war ended. It was then succeeded by that quiet which comes to us all, one day.

The first book, by Shaw, is about the War of Two Brothers. The other two books are from the Duke of Wellington's earlier experiences in Portugal. I have written before that Sir John Campbell was mentioned favourably in dispatches by Wellesley, late the Duke, but this may not be true, or it may be true but some of the mentions may refer to other Campbells. I post links to some of the books here in case anyone is interested in finding out more.

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

The young Portuguese bride of Sir John Campbell: Dona Maria Brigida

I have mentioned a few things about Sir John Campbell, KB, KCTS, and left off suggesting that the KCTS (Knight Commander of the Tower and the Sword, Portugal) shaped his life.

As far as I can tell, Sir John Campbell stayed in Portugal after the Peninsular Wars, on loan to the Portuguese army until 1820. He left when the constitutionalists started to become too heated. When he returned to England, he lived in Baker Street with his Portuguese wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, and Elizabeth, their daughter, who was born in Lisbon in 1818.

Sir John and Maria Brigida were married in 1816. She was 18 years old. He was 36.

Upon their return to England in 1820, or perhaps shortly before, their son, John David Campbell, was born. Elizabeth and John David are the only children I know of in this family.

Sir John was given what sounds like a reasonably quiet job in England, in command of the 75th Regiment of Foot while they were at home and not off fighting abroad. This is a famous regiment (the Gordon Highlanders) but during Sir John's tenure, I have the impression nothing much happened. (Another avenue for the eager military historian to pursue.)

I wish I could draw the curtain here and say they lived happily ever after. At this point, Portugal was experiencing unrest but not war, and Sir John had a comfortable family life in London, from the sounds of it.

Alas.

Some day I would like to go to the Parish Church in Marylebone.

View Larger Map

I've seen it from the outside without knowing (nor, at that time, caring) but haven't gone in.

As far as I can tell, there is still a plaque on the east wall, reading as follows.

Having lost his wife and little boy between 1821 and 1824, Sir John retired from the army and sold his commission by the 1st of October, 1824. Thus he and young Elizabeth (only 6 years old when her brother died; motherless since age 3) were apparently left alone.

There is always the possibility that Sir John married a second time during this period. I have found no mention of such an event, however, and the notes in biographic sources are consistent in saying he had two wives.

At this point my impression of Sir John is that he was living quietly and was enjoying a life of reasonably high social standing. His sisters and brothers appeared to have married well, and he probably had good family connections on his mother's side (the Pitcairns). I would say the same of his father's, but I haven't been able to trace them back with any confidence.

Things were about to change, and the KCTS was going to make a big difference in Sir John's life.

As far as I can tell, Sir John Campbell stayed in Portugal after the Peninsular Wars, on loan to the Portuguese army until 1820. He left when the constitutionalists started to become too heated. When he returned to England, he lived in Baker Street with his Portuguese wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, and Elizabeth, their daughter, who was born in Lisbon in 1818.

Sir John and Maria Brigida were married in 1816. She was 18 years old. He was 36.

Upon their return to England in 1820, or perhaps shortly before, their son, John David Campbell, was born. Elizabeth and John David are the only children I know of in this family.

Sir John was given what sounds like a reasonably quiet job in England, in command of the 75th Regiment of Foot while they were at home and not off fighting abroad. This is a famous regiment (the Gordon Highlanders) but during Sir John's tenure, I have the impression nothing much happened. (Another avenue for the eager military historian to pursue.)

I wish I could draw the curtain here and say they lived happily ever after. At this point, Portugal was experiencing unrest but not war, and Sir John had a comfortable family life in London, from the sounds of it.

Alas.

Some day I would like to go to the Parish Church in Marylebone.

View Larger Map

I've seen it from the outside without knowing (nor, at that time, caring) but haven't gone in.

As far as I can tell, there is still a plaque on the east wall, reading as follows.

"To the memory of

Dona Maria Brigida do Faria

E Lacerda

Wife of

Sir John Cambell, K.C.T.S.

Lieut Col in the British, and Maj Gen in the Portuguese Service.

She died much lamented

on the 22nd Jan 1821, in the 24th Year of her age;

Her remains are deposited in a vault of this Church.

Also of

John David Campbell

Son of the above who died 28 May 1824

Aged 3 years and 9 months"

http://www.archive.org/stream/miscellaneagene01howagoog#page/n31/mod e/2up

Having lost his wife and little boy between 1821 and 1824, Sir John retired from the army and sold his commission by the 1st of October, 1824. Thus he and young Elizabeth (only 6 years old when her brother died; motherless since age 3) were apparently left alone.

There is always the possibility that Sir John married a second time during this period. I have found no mention of such an event, however, and the notes in biographic sources are consistent in saying he had two wives.

At this point my impression of Sir John is that he was living quietly and was enjoying a life of reasonably high social standing. His sisters and brothers appeared to have married well, and he probably had good family connections on his mother's side (the Pitcairns). I would say the same of his father's, but I haven't been able to trace them back with any confidence.

Things were about to change, and the KCTS was going to make a big difference in Sir John's life.

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Sir John Campbell, Knight Bachelor, and his wife Harriet Maria: what probate told me

In 1851 and 1861, Sir John Campbell and his wife Harriet Maria were living at 51 Charles Street, Berkeley Square, London with four servants in 1851 and two of the same plus two new ones in 1861.

My first impression was that this was a couple who had spent 50 or 60 years together. There was no mention of children in either census, but as Sir John and Harriet were each born in about 1781, any children they had may well have been married and gone by 1800 to 1810.

Sir John's presumably self-described occupation changed just a little over the 10 years. He was a Knight Bachelor and a retired Lieutenant Colonel from the Army.

The fact that he was knighted gave me some hope of finding a formal and detailed biography somewhere, and I wasn't disappointed. Sadly, the name "John Campbell" is hardly rare. Even "Sir John Campbell" born around 1780 isn't unique. Throughout, I've had to be careful not to get mixed up with other Sir John Campbells and other army officers of the same time, named Campbell.

Knowing that Sir John and Lady Campbell were each 80 years old in the 1861 census, it made sense to look for information about their respective deaths first. This is following the principle of working from the known to the unknown, a good basic research strategy.

Sir John Campbell: Information from probate

I am quite grateful that the National Probate Calendar for England is available online through Ancestry.com. This index lists all the grants to people who acted as executors and administrators of estates. It often gives a few good clues about where a person spent the latter part of their life, how much money they had at the end, and often identifies one or more close relatives.

A quick search for Sir John Campbell dying in 1861 or later turned up an entry in the Wills of 1864.

Instantly, I had a positive identification:

Sir John Campbell, Knight, late of 51 Charles Street;

and some new information:

It will be confusing to start into Lady Campbell's details here but don't worry, I did the same for her and will be back with more about her, too.

My first impression was that this was a couple who had spent 50 or 60 years together. There was no mention of children in either census, but as Sir John and Harriet were each born in about 1781, any children they had may well have been married and gone by 1800 to 1810.

Sir John's presumably self-described occupation changed just a little over the 10 years. He was a Knight Bachelor and a retired Lieutenant Colonel from the Army.

The fact that he was knighted gave me some hope of finding a formal and detailed biography somewhere, and I wasn't disappointed. Sadly, the name "John Campbell" is hardly rare. Even "Sir John Campbell" born around 1780 isn't unique. Throughout, I've had to be careful not to get mixed up with other Sir John Campbells and other army officers of the same time, named Campbell.

Knowing that Sir John and Lady Campbell were each 80 years old in the 1861 census, it made sense to look for information about their respective deaths first. This is following the principle of working from the known to the unknown, a good basic research strategy.

Sir John Campbell: Information from probate

I am quite grateful that the National Probate Calendar for England is available online through Ancestry.com. This index lists all the grants to people who acted as executors and administrators of estates. It often gives a few good clues about where a person spent the latter part of their life, how much money they had at the end, and often identifies one or more close relatives.

A quick search for Sir John Campbell dying in 1861 or later turned up an entry in the Wills of 1864.

Instantly, I had a positive identification:

Sir John Campbell, Knight, late of 51 Charles Street;

and some new information:

- He died 19 December 1863 at his home on Charles Street;

- He was Knight Commander of the Order of the Tower and Sword of Portugal;

- His effects were originally valued at under £8,000. In March 1865, the value was changed to under £10,000.

- His executors were Richard Onslow of Wandsworth, Surrey, Esquire, and William Campbell Onslow of 28 Leinster Gardens, Middlesex, Esquire, a retired Lieutenant Colonel of Her Majesty's Indian Army.

It will be confusing to start into Lady Campbell's details here but don't worry, I did the same for her and will be back with more about her, too.

Labels:

1851,

1861,

C19,

campbell,

census,

charles street,

england,

history,

st george hanover square,

tracing your roots,

uk,

upper class,

using ancestry.com

Saturday, March 5, 2011

John Burgoyne Blackett at 2 Charles Street in the late 1840s

This is a listing from the Northumberland Archives, via Access to Archives, a very useful service indeed.

Here's exactly what's on the screen:

"Notebook (vol. IV) comprising copies of letters from J[ohn] B[urgoyne] Blackett, initially at 2 Charles Street, Berkeley Square, then at 10 Eaton Place to Congreve, May 1848-Dec. 1851. Concerning politics, literary matters, mutual friends, foreign affairs, university reform, possible personal insolvency, retrenchment in standard of living. A group of undated letters at the end, perhaps c.1844, predate the main section. ZBK/C/1/B/3/1/9 [n.d.]"

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/records.aspx?cat=155-zbk_3-1&cid=1-1-2-3-1#1-1-2-3-1

Why it matters to our story

You may notice that in 1848 when the letters started, Blackett was living at 2 Charles Street. He was also the Member of Parliament for Northumberland South from 1852 to 1856. His successor as the MP for the riding was George Ridley, who lived at 2 Charles Street later.

Maybe No. 2 was rented for whomever represented Northumberland South from time to time. But, the dates of the letters from Blackett at No. 2 don't match the dates of his time as an MP. Perhaps the connection is more to do with being from the nobility of Northumberland.

It raises the question of what Henry Fleming was doing there on census night in 1871, though. Guest of an absent MP, perhaps?

Blackett later lived at 10 Eaton Place, London, and for some reason I think I have run across Eaton Place in this research already. Will have to keep my eyes open.

Connection between Blackett and the March family (of No. 1 Charles Street, in 1871)

This is one of those "the world is a pretty small place" things, but that's what happens when you have people descended from William the Conqueror, Plantagenets, and so on.

The name "Umfreville" appears in both the Blackett and March families. For the Blacketts, it's way back around the 1500s. For the Marches, one of Thomas Charles March's sisters married a Yorkshire clergyman (of a titled family, if I remember correctly), and their sons had Umfreville as a middle name. The spelling varies, Umfreville, Umfraville.

A distant connection.

Here's exactly what's on the screen:

"Notebook (vol. IV) comprising copies of letters from J[ohn] B[urgoyne] Blackett, initially at 2 Charles Street, Berkeley Square, then at 10 Eaton Place to Congreve, May 1848-Dec. 1851. Concerning politics, literary matters, mutual friends, foreign affairs, university reform, possible personal insolvency, retrenchment in standard of living. A group of undated letters at the end, perhaps c.1844, predate the main section. ZBK/C/1/B/3/1/9 [n.d.]"

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/records.aspx?cat=155-zbk_3-1&cid=1-1-2-3-1#1-1-2-3-1

Why it matters to our story

You may notice that in 1848 when the letters started, Blackett was living at 2 Charles Street. He was also the Member of Parliament for Northumberland South from 1852 to 1856. His successor as the MP for the riding was George Ridley, who lived at 2 Charles Street later.

Maybe No. 2 was rented for whomever represented Northumberland South from time to time. But, the dates of the letters from Blackett at No. 2 don't match the dates of his time as an MP. Perhaps the connection is more to do with being from the nobility of Northumberland.

It raises the question of what Henry Fleming was doing there on census night in 1871, though. Guest of an absent MP, perhaps?

Blackett later lived at 10 Eaton Place, London, and for some reason I think I have run across Eaton Place in this research already. Will have to keep my eyes open.

Connection between Blackett and the March family (of No. 1 Charles Street, in 1871)

This is one of those "the world is a pretty small place" things, but that's what happens when you have people descended from William the Conqueror, Plantagenets, and so on.

The name "Umfreville" appears in both the Blackett and March families. For the Blacketts, it's way back around the 1500s. For the Marches, one of Thomas Charles March's sisters married a Yorkshire clergyman (of a titled family, if I remember correctly), and their sons had Umfreville as a middle name. The spelling varies, Umfreville, Umfraville.

A distant connection.

Labels:

1850s,

1871 census,

ancestry,

blackett,

britain,

census,

charles street,

henry fleming,

history,

london,

mp,

tracing your roots,

uk,

united kingdom,

upper class,

victorian

Friday, February 25, 2011

No. 2 Charles Street Berkeley Square, Mayfair, London, in 1871

The last seven posts, starting with

Thomas March of 1 Charles Street: One degree from Queen Victoria

have looked closely at the family who occupied No.1 Charles Street according to the 1871 census.

Charles Street runs from the south west corner of Berkeley Square, and from what I've seen, it was a pretty good neighbourhood back in 1871.

We continue the exploration with the second house on the street. Here's the Google Maps image as it now is.

View Larger Map

And the current Google Street View picture, with No. 1 on the right (Thomas C. March house in 1871) and No. 2, the blue one, on the left.

View Larger Map

Link in case map isn't visible: 2 Charles Street, Mayfair, and the link to the Street View.

Living at No. 2, in 1871, the census says this.

No. 2: Henry Flemming, 59, unmarried, Civil Servant, Secretary of the Poor Law Board

1 Family, namely Henry himself.

2 Servants, James Austen, 50, and Martha Newman, 17, both unmarried.

Citation from Ancestry.co.uk: Class: RG10; Piece: 102; Folio: 75; Page: 31; GSU roll: 838762.

There's a mention here on p. 522 of The British Medical Journal, May 23, 1868:

"IO. Mr. Flemming, Secretary of the Poor-law Board, acknowledges

on February 20th, I867, the receipt of Mr. Trevor's last letter."

The spelling of "Flemming", however, is not consistent in the records. In the majority of cases I've seen so far, it's been spelled with only one "m", "Fleming".

Henry Fleming was a rather interesting fellow, from another interesting family. This family will take us to the poorhouse and to the last gasps of the slave trade.

Our peek at the houses of Charles Street, Berkeley Square in 1871 began at No. 1: Thomas March of 1 Charles Street: One degree from Queen Victoria.

Before that, we started with the Stoker family: Bram Stoker, author of Dracula in public records: BMD (Birth, Marriage, Death).

Next: Who was Henry Fleming? A dandy? A heartless villain? Both? Neither? More history from Charles Street, Berkeley Square.

Thomas March of 1 Charles Street: One degree from Queen Victoria

have looked closely at the family who occupied No.1 Charles Street according to the 1871 census.

Charles Street runs from the south west corner of Berkeley Square, and from what I've seen, it was a pretty good neighbourhood back in 1871.

We continue the exploration with the second house on the street. Here's the Google Maps image as it now is.

View Larger Map

And the current Google Street View picture, with No. 1 on the right (Thomas C. March house in 1871) and No. 2, the blue one, on the left.

View Larger Map

Link in case map isn't visible: 2 Charles Street, Mayfair, and the link to the Street View.

Living at No. 2, in 1871, the census says this.

No. 2: Henry Flemming, 59, unmarried, Civil Servant, Secretary of the Poor Law Board

1 Family, namely Henry himself.

2 Servants, James Austen, 50, and Martha Newman, 17, both unmarried.

Citation from Ancestry.co.uk: Class: RG10; Piece: 102; Folio: 75; Page: 31; GSU roll: 838762.

There's a mention here on p. 522 of The British Medical Journal, May 23, 1868:

"IO. Mr. Flemming, Secretary of the Poor-law Board, acknowledges

on February 20th, I867, the receipt of Mr. Trevor's last letter."

The spelling of "Flemming", however, is not consistent in the records. In the majority of cases I've seen so far, it's been spelled with only one "m", "Fleming".

Henry Fleming was a rather interesting fellow, from another interesting family. This family will take us to the poorhouse and to the last gasps of the slave trade.

Our peek at the houses of Charles Street, Berkeley Square in 1871 began at No. 1: Thomas March of 1 Charles Street: One degree from Queen Victoria.

Before that, we started with the Stoker family: Bram Stoker, author of Dracula in public records: BMD (Birth, Marriage, Death).

Next: Who was Henry Fleming? A dandy? A heartless villain? Both? Neither? More history from Charles Street, Berkeley Square.

Labels:

1871 census,

ancestry,

britain,

charles street,

england,

family history,

henry fleming,

henry flemming,

history,

london,

mayfair,

poor law,

uk,

united kingdom

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)