There are a few things I'd like to pass along about this satire.

The reference for the actual article is "History of the Tête-à-tête annexed: or, Memoirs of P_____ M______, Esq; and Miss Clara H_____d. (No. 4, 5)" in The Town and Country Magazine of February 1776, at page 65, with the engravings on the page between 64 and 65. The page with the engravings shows a date of March 1, 1776, but the online version of the magazine is quite clearly the February 1776 issue. It caused me a little confusion when I found the article referred to as being in the March edition, so, don't do what I did and go looking in March. The thing you want is in February.

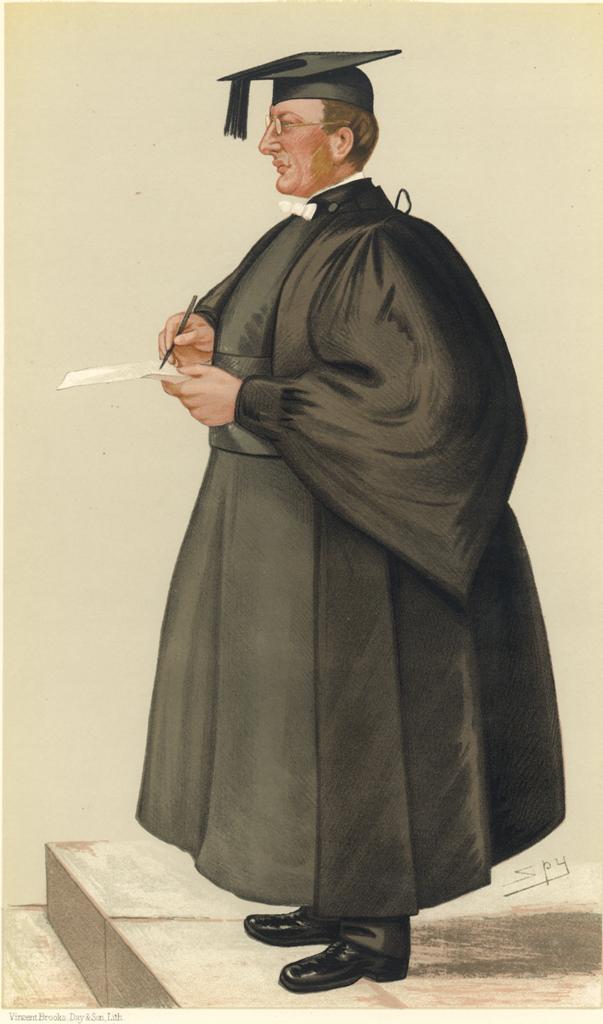

It's a bit confusing that the man is identified (cryptically but not impenetrably) as Philip Meadows, Deputy Ranger of Richmond Park. Philip Meadows, whose name often uses the Meadows spelling, unlike most other family members, who show as Medows, was the father of Evelyn Philip Medows. Philip Meadows Esquire was born in 1708 and died in 1781. His wife, Lady Frances Pierrepont, lived from 1713 to 1795. While it is entirely possible that Philip had a mistress or two in his day (I've seen nothing either way on this), Philip was probably more than 40 years older than Clara Hayward, and at the time of these portraits in 1776, would have been 63 years old. I'm thinking that such a gap in age, had it existed, would have been remarked upon in the satire, and also that this picture looks like a younger man.

Evelyn Philip Medows, on the other hand, lived from 1736 to 1826, making him about 14 years older than Clara and aged 40 during the heyday of their romance. Some records say that Evelyn married Margaret Cramond, and in one of the Duchess of Kingston's letters, she mentions his wife. However, when this marriage occurred and how long it lasted, I don't know. I haven't seen records of any surviving children.

I don't know why Town and Country identified him as Philip Meadows, nor do I know whether Evelyn Medows ever held the position of Deputy Ranger of Richmond Park. It is quite possible that he did: his father had that role, as did his uncle Sidney Medows (from whom Evelyn eventually did inherit a substantial fortune, including his house in Charles Street). John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, was Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1762-1763, and Ranger of Richmond Park from 1761 (whether until his death in 1792 or some earlier date, I don't know, but he occupied White Lodge in the park during this whole time, apparently).

The Earl of Bute was connected by marriage to the Pierrepont family (notably to Evelyn Pierrepont, Duke of Kingston, brother to Lady Frances Medows nee Pierrepont) and thus to the Medows. Evelyn Medows was the eldest son of Lady Frances, and the eldest nephew of the childless Duke, making him the heir apparent of the Pierreponts. It wouldn't surprise me if the Earl favoured him with a home at Richmond Park. However, I have no proof at all that Evelyn was ever the Deputy Ranger. I'm casting about for an explanation as to why Town and Country gave the description they did.

At any rate, the satire tells of how the young man was a favourite hunting companion of the King of Prussia and had visited Voltaire in France. Disappointed in love in England, he took a three-month tour of the country, eventually settling into his post at Richmond Park. He saw the lady on the stage and was smitten; took her to Richmond and there they lived in rural contentment.

There is no question about the Town and Country lady's identity. She is Clara Hayward, an actress about whom I've only found snippets on the Web. In the satire, her story is one of rags to riches, or at least from rags to comfort at the expense of a series of men, including a lawyer and a dashing officer. She appears as a supporting character in a variety of books about the life and times of women in the 18th century and I believe there is much more known about her than I have found in my Web surfing. Here are a few quotes about Clara.

Early training

From an excerpt of the scanned version of England's mistress: the infamous life of Emma Hamilton, by Kate Williams, published by Hutchinson, 2006; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books:

Aspiring actresses competed for a place at Kelly's for many stars of the eighteenth-century London stage, including Mrs Abington and Clara Hayward, had learnt posture and dance at Arlington Street.

***

From an excerpt of the scanned version of Ladies fair and frail: sketches of the demi-monde during the eighteenth century, by Horace Bleackley, published by Dodd, Mead and Company, 1926; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books.

This [the 1760s] was the time when giddy Nan Catley was at her zenith, when spendthrift Baddeley had reached the height of her fame, when the youthful Clara Hayward had begun to conquer all hearts with her dainty ways. Nevertheless, from the year 1769 till the year 1773 Miss Kennedy remained as great a favourite with the bucks and bloods as any of these pretty actresses.

****

1770 theatrical debut

From an excerpt of the scanned version of The Letters of David Garrick, by George Morrow Kahrl, published by Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books.

Clara Hayward made her debut at Drury Lane on Oct. 27, 1770; she appeared in a number of roles, with varying success, and after March 1772 her name no longer appears on the Drury Lane playbills (Theatrical Biography, 1772, I, 20-23 …

1772 with Evelyn Medows

From A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Volume 7, Habgood to Houbert: Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800, by Philip H. Highfill, Kalman A. Burnim, Edward A. Langhans, SIU Press, 1982; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books:

Clara Hayward (fl. 1770—1772) actress. The 1772 edition of Theatrical Biography reported that Miss Clara Hayward came from an obscure and humble background (her mother dealt in oysters, said the Town and Country Magazine in February 1776).

She attracted the attention of a young guards officer who initially wished only "temporary gratification," but, charmed with her mind as well as her person, he taught her to read. When he left her, she "fled to her books as an asylum, which she occasionally relieved with a lover." Her reading attracted her to tragedy and to the stage, and through a friend who knew Samuel Foote, she was introduced to theatrical circles. Sheridan "voluntarily became her instructor in the histrionic mysteries," and on 9 July 1770 she made her first appearance on any stage at the Haymarket Theatre playing Calista in The Fair Penitent.

[I am assuming from the context that this part of the quote from the Theatrical Biography (1772) describes her relationship with Evelyn Medows:] She accepted the heart of a young gentleman in the guards, as remarkable for the oddity of his taste in dress, as the delicacy of his person; which last is so remarkable that he has often gone into keeping himself when his finances have run short. Such is her present connexion.

1774 party girl (perhaps earlier)

Memoirs of William Hickey (1749 - 1830) Volume 1 mentions Clara Hayward three times, from around 1774.

He refers to her as one of his favourites (among 20 or so) who was, to paraphrase, warmer in bed than one Emily, to whom he is drawing a comparison. (All 20-plus are warmer than Emily.) The timing here seems confusing as in 1772 and 1776, the publications of the day have Clara linked to Evelyn Medows.

In planning a very expensive party to be held at Richmond-upon-Thames, Hickey lists the beautiful ladies he will invite, Clara among them, " … each of whom could with composure carry off her three bottles [of wine]."

From an excerpt of the scanned version of Ladies fair and frail: sketches of the demi-monde during the eighteenth century, by Horace Bleackley, published by Dodd, Mead and Company, 1926; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books.

In the Morning Post of the 27th of January 1776 there appeared a description of one of the numerous masquerades at the Pantheon in Oxford Street, and as usual the "free and easy" portion of the company was mentioned in the report. Among these were several handsome women, whose names were familiar to everyone. The "laughter-loving" Clara Hayward, as the newspapers were fond of styling her, had risen to fame half-a-dozen years before, when she appeared as Calista in "The Fair Penitent " at Foote's Theatre in the Haymarket, where she had shown sufficient ability to secure an engagement at Drury Lane ; and now having left the stage she had become a more or less inconstant mistress of Evelyn Meadows, the favourite nephew and presumptive heir of the eccentric Duchess of Kingston. The graceful Harriet Powell, equally frail and famous, whose winsome face was portrayed in many a mezzotint, had spent her early youth as an inmate of Mrs Hayes's disreputable establishment in King's Place, but now at last she had become faithful to one man, and was keeping house with Lord Seaforth, the creator of a famous regiment.

and

That she [Grace Dalrymple Eliot] should have been regarded as a formidable rival to Clara Hayward and Charlotte Spencer indicates to what depths she had sunk.

As we know from the lawsuit in which Evelyn Medows (the usual spelling) effectively accused the Duchess of Kingston of bigamy in order to undo the will of the late Duke, who had disinherited him, Evelyn was hardly the favourite nephew and presumptive heir of the Duchess at all times. However, her attitude toward him was far less negative than might be thought, and she did indeed seem to favour him in the years after the trial, up to her death. (I think they were kindred spirits.)

In addition to the Morning Post item mentioned, the Town and Country Magazine profile of Clara and Evelyn appeared in February 1776.

Regarding Charlotte Hayes and her establishment, Jan Toms has presented a few interesting facts in her short article, "The 18th Century Brothel – How Some Girls Won Fame and Fortune".

From an excerpt of the scanned version of Thomas Gainsborough: his life and work, by Mary Woodall, published by Phoenix House, 1949; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books.

…'In the following year [appears to refer to 1778], eleven portraits and two landscapes were sent to the Academy from Schomberg House. He has, it is plain, been visited by Miss Dalrymple, Clara Hayward and another well-known character of the same stamp.'(1) The portraits were considered to be remarkably strong likenesses, although the real faces of the 'painted ladies' had not been seen for many years.

As a side note, Clara Hayward appears as a character in a play of the early 1950s by Cecil Beaton, about Gainsborough and his family, The Gainsborough Girls, later re-presented as Landscape with Figures.

From an excerpt of the scanned version of The Letters of David Garrick, by George Morrow Kahrl, published by Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books.

Clara Hayward made her debut at Drury Lane on Oct. 27, 1770; she appeared in a number of roles, with varying success, and after March 1772 her name no longer appears on the Drury Lane playbills (Theatrical Biography, 1772, I, 20-23 …

****

1772 with Evelyn Medows

From A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Volume 7, Habgood to Houbert: Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800, by Philip H. Highfill, Kalman A. Burnim, Edward A. Langhans, SIU Press, 1982; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books:

Clara Hayward (fl. 1770—1772) actress. The 1772 edition of Theatrical Biography reported that Miss Clara Hayward came from an obscure and humble background (her mother dealt in oysters, said the Town and Country Magazine in February 1776).

She attracted the attention of a young guards officer who initially wished only "temporary gratification," but, charmed with her mind as well as her person, he taught her to read. When he left her, she "fled to her books as an asylum, which she occasionally relieved with a lover." Her reading attracted her to tragedy and to the stage, and through a friend who knew Samuel Foote, she was introduced to theatrical circles. Sheridan "voluntarily became her instructor in the histrionic mysteries," and on 9 July 1770 she made her first appearance on any stage at the Haymarket Theatre playing Calista in The Fair Penitent.

[I am assuming from the context that this part of the quote from the Theatrical Biography (1772) describes her relationship with Evelyn Medows:] She accepted the heart of a young gentleman in the guards, as remarkable for the oddity of his taste in dress, as the delicacy of his person; which last is so remarkable that he has often gone into keeping himself when his finances have run short. Such is her present connexion.

***

1774 party girl (perhaps earlier)

Memoirs of William Hickey (1749 - 1830) Volume 1 mentions Clara Hayward three times, from around 1774.

He refers to her as one of his favourites (among 20 or so) who was, to paraphrase, warmer in bed than one Emily, to whom he is drawing a comparison. (All 20-plus are warmer than Emily.) The timing here seems confusing as in 1772 and 1776, the publications of the day have Clara linked to Evelyn Medows.

In planning a very expensive party to be held at Richmond-upon-Thames, Hickey lists the beautiful ladies he will invite, Clara among them, " … each of whom could with composure carry off her three bottles [of wine]."

****

1776 with Evelyn MedowsFrom an excerpt of the scanned version of Ladies fair and frail: sketches of the demi-monde during the eighteenth century, by Horace Bleackley, published by Dodd, Mead and Company, 1926; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books.

In the Morning Post of the 27th of January 1776 there appeared a description of one of the numerous masquerades at the Pantheon in Oxford Street, and as usual the "free and easy" portion of the company was mentioned in the report. Among these were several handsome women, whose names were familiar to everyone. The "laughter-loving" Clara Hayward, as the newspapers were fond of styling her, had risen to fame half-a-dozen years before, when she appeared as Calista in "The Fair Penitent " at Foote's Theatre in the Haymarket, where she had shown sufficient ability to secure an engagement at Drury Lane ; and now having left the stage she had become a more or less inconstant mistress of Evelyn Meadows, the favourite nephew and presumptive heir of the eccentric Duchess of Kingston. The graceful Harriet Powell, equally frail and famous, whose winsome face was portrayed in many a mezzotint, had spent her early youth as an inmate of Mrs Hayes's disreputable establishment in King's Place, but now at last she had become faithful to one man, and was keeping house with Lord Seaforth, the creator of a famous regiment.

and

That she [Grace Dalrymple Eliot] should have been regarded as a formidable rival to Clara Hayward and Charlotte Spencer indicates to what depths she had sunk.

As we know from the lawsuit in which Evelyn Medows (the usual spelling) effectively accused the Duchess of Kingston of bigamy in order to undo the will of the late Duke, who had disinherited him, Evelyn was hardly the favourite nephew and presumptive heir of the Duchess at all times. However, her attitude toward him was far less negative than might be thought, and she did indeed seem to favour him in the years after the trial, up to her death. (I think they were kindred spirits.)

In addition to the Morning Post item mentioned, the Town and Country Magazine profile of Clara and Evelyn appeared in February 1776.

Regarding Charlotte Hayes and her establishment, Jan Toms has presented a few interesting facts in her short article, "The 18th Century Brothel – How Some Girls Won Fame and Fortune".

***

1778 or possibly earlier, painted by Gainsborough

From an excerpt of the scanned version of Thomas Gainsborough: his life and work, by Mary Woodall, published by Phoenix House, 1949; excerpt in scanned version viewed courtesy Google Books.

…'In the following year [appears to refer to 1778], eleven portraits and two landscapes were sent to the Academy from Schomberg House. He has, it is plain, been visited by Miss Dalrymple, Clara Hayward and another well-known character of the same stamp.'(1) The portraits were considered to be remarkably strong likenesses, although the real faces of the 'painted ladies' had not been seen for many years.

As a side note, Clara Hayward appears as a character in a play of the early 1950s by Cecil Beaton, about Gainsborough and his family, The Gainsborough Girls, later re-presented as Landscape with Figures.

***