This is part of my ongoing exploration of Charles Street, mainly in the 1871 census, though as it happens Sir John died in 1863.

I became curious about Sir John's wealth (or lack of it) and where it went after his death. One avenue I explored was the obvious one: his descendants.

Sir John's Portuguese wife and young son died when the boy was young, leaving only a daughter, Elizabeth Campbell (1818 - 1883). During Elizabeth's childhood, Sir John was away fighting on what ended up being the losing side of a revolution in Portugal. He then spent some more time there as a prisoner of war, while the British government washed their hands of him.

My suspicion is that Elizabeth may have been raised during his absence by one of Sir John's two sisters, Elizabeth. (His other sister, Marianna, died in 1810.) The two sisters had married two brothers from a very good family. Elizabeth married Reverend George Walton Onslow (1768 - 1844) and had at least 11 children.

One clue to the connection between this Elizabeth and Sir John that helped me find her and then figure out she was his sister, was that one of the children's name was Pitcairn Onslow. Sir John's mother was Annie Pitcairn and the name is a handy finding aid, especially when wallowing in a soup of Campbells.

Marianna Campbell married Reverend Arthur Onslow (1773 - 1851), and had at least three children. One, William Campbell Onslow, has the name of his grandfather (William Campbell) embedded in his own name.

In 1844, at the age of 26, Elizabeth (Sir John's daughter) married Edmond Sexten Pery Calvert (1797 - 1866), who would have been 46 or 47 by then. As far as I know, she was his first wife. The Calvert family has a lot of interesting connections, but I will try my hardest not to tell you about each and every one.

The Family Life of Elizabeth and Edmond Sexten Pery Calvert

It is hard for me to prove this next bit with absolute certainty, but my interpretation of the evidence suggests that E&E's first child was actually not one child, but twins. Felix Calvert was born in the spring of 1845 and died very soon thereafter. It looks like Felix had a twin sister, Frances Elise Calvert, who also died very soon after birth.

The next year, a daughter was born and survived. Her name was Frances Elizabeth Calvert, born on August 9, 1846. Her birth was noted in the magazine The Patrician.

A little brother, also called Felix, arrived on September 12, 1847. One source of confusion in researching family history is that names were recycled within the same generation, as this branch of the Calvert family demonstrates. In fact, from one generation to the next, the name "Felix" is very common in the Calverts and also in their relatives, the Ladbrokes.

The last child of Elizabeth Campbell Calvert of whom I'm aware of was Walter, born on September 4, 1849 at Charles Street. I would be on solid ground in suggesting this event happened at the home of Sir John Campbell and his second wife, Harriet Maria (nee Norie), at 51 Charles Street.

Frances Elise died before she was 10 years old, in the spring of 1856.

Her two brothers, however, did live quite long lives. Their father, Edmond Sexten Pery Calvert, died in 1866 at 68. Felix was 19, Walter 17 and their mother, Elizabeth 48 when that happened. She did not remarry.

For much of her life, Elizabeth lived with her son Felix. She died at 65 in late December of 1883. Felix lived on, farming the Calvert estate at Furneux Pelham in Hertfordshire until his death, unmarried, at age 62. He was a Justice of the Peace.

The youngest, Walter Campbell Calvert, went into the military and reached the rank of Captain in the 5th Dragoon Guards. He died in 1932, having had the longest life of them all, at 82. He too appears to have been unmarried and as far as I know, left no children.

And thus the line of Sir John Campbell, KCTS, expired. There are many collateral descendants – nephews, nieces, cousins, and so on – but no one who traces back to Sir John directly.

What happened to the family fortune?

The question to ask before that one is, "Was there a family fortune?" I have looked into this and the answers were surprising. That's for another day, though.

Odds and ends that turn up in the course of doing family history and genealogy research. Every name has a story. At least one.

Saturday, June 25, 2011

Monday, June 20, 2011

Why you should keep on digging when researching family history

I had the birth, marriage, and death information for Sir John Campbell, KCTS some time ago. Why keep going?

There are a few reasons, but here is one of them: to learn what kind of man he was.

I've made inferences, which is really all I can do, given the lack of direct evidence about the man. However, there are a few eyewitnesses who described him as a soldier (Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, commended him in his reports of battles in Portugal), as a prisoner of war in Portugal, and even in the House of Lords, he was a topic of conversation, albeit perhaps as more of a political football than as an individual.

None of this shed light on his home life, which is what I hoped to find out about as I continued the research.

Through a lot of persistent searching for anything about him, I thought I had found pretty much all I could in terms of books or articles mentioning him specifically, to the extent that these appear online. That will change with time, and there's a lesson: go back in a year, and then in another year, and another, until you are satisfied. More information becomes available all the time. Never close the door.

I also learned the value of tracking relatives beyond the immediate family. Well, "learned" isn't really the right word. "Proved" might be closer.

The best nugget came from searching his name in conjunction with the name of a house, Hunsdon House. How did I know to do that search? Because I traced Sir John's daughter, Elizabeth, his only surviving child. She married into the Calvert family, and lived for a time at their property, Hunsdon House.

Pushing further into the Calverts revealed two interesting sources: the published memoirs of Elizabeth's mother-in-law, Lady Frances Calvert (nee Pery), and the fact that one of Elizabeth's nephews became a very well-known public figure. He was Edmond Warre (1837 to 1920) who is remembered as a famous oarsman for Oxford and a long-time master and then Headmaster (1880 to 1909) of Eton College.

In Edmond Warre, D.D., C.B., C.V.O.: Sometime Headmaster and Provost of Eton College, by Charles Robert Leslie Fletcher (J. Murray, 1922), the Google Books copy, I found this passage.

"… Sir John Campbell (a Peninsular veteran who had married a Portuguese lady); he was not such a favourite with the children as Uncle Felix".

Because I don't have the actual book, just snippets, I can't easily see the whole page. I'm working on digging up interesting bits from the book for my next post.

There are a few reasons, but here is one of them: to learn what kind of man he was.

I've made inferences, which is really all I can do, given the lack of direct evidence about the man. However, there are a few eyewitnesses who described him as a soldier (Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, commended him in his reports of battles in Portugal), as a prisoner of war in Portugal, and even in the House of Lords, he was a topic of conversation, albeit perhaps as more of a political football than as an individual.

None of this shed light on his home life, which is what I hoped to find out about as I continued the research.

Through a lot of persistent searching for anything about him, I thought I had found pretty much all I could in terms of books or articles mentioning him specifically, to the extent that these appear online. That will change with time, and there's a lesson: go back in a year, and then in another year, and another, until you are satisfied. More information becomes available all the time. Never close the door.

I also learned the value of tracking relatives beyond the immediate family. Well, "learned" isn't really the right word. "Proved" might be closer.

The best nugget came from searching his name in conjunction with the name of a house, Hunsdon House. How did I know to do that search? Because I traced Sir John's daughter, Elizabeth, his only surviving child. She married into the Calvert family, and lived for a time at their property, Hunsdon House.

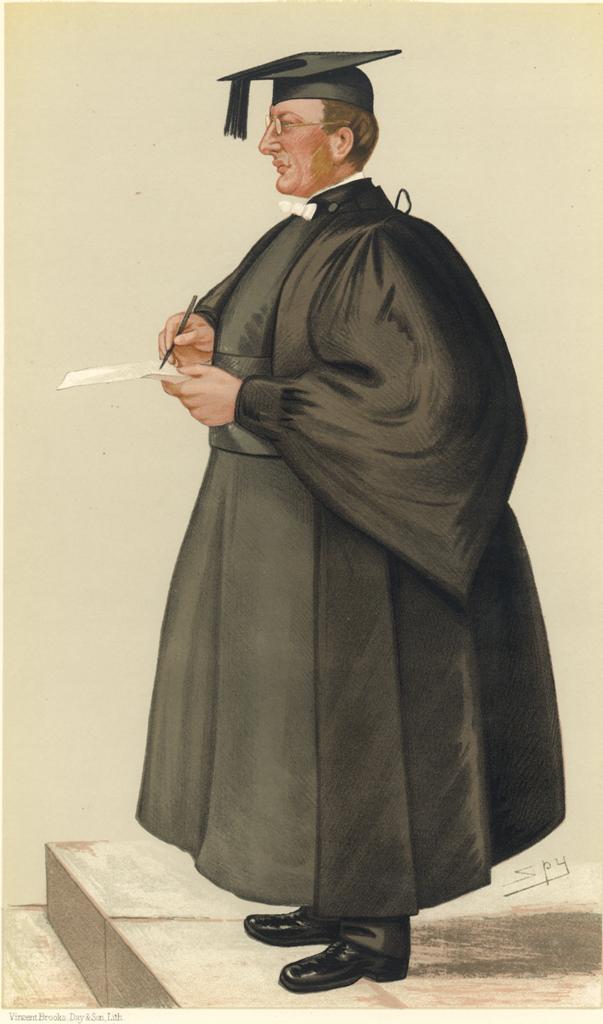

Pushing further into the Calverts revealed two interesting sources: the published memoirs of Elizabeth's mother-in-law, Lady Frances Calvert (nee Pery), and the fact that one of Elizabeth's nephews became a very well-known public figure. He was Edmond Warre (1837 to 1920) who is remembered as a famous oarsman for Oxford and a long-time master and then Headmaster (1880 to 1909) of Eton College.

| |

| Edmond Warre, "The Head". In Vanity Fair magazine, June 20, 1885. |

"… Sir John Campbell (a Peninsular veteran who had married a Portuguese lady); he was not such a favourite with the children as Uncle Felix".

Because I don't have the actual book, just snippets, I can't easily see the whole page. I'm working on digging up interesting bits from the book for my next post.

Labels:

edmond warre,

england,

eton college,

family history,

genealogy,

hertfordshire,

hundson,

sir john campbell,

uk

Thursday, June 2, 2011

A wonderful newspaper clipping from 1835

This comes from the The Court Journal: Court circular and fashionable gazette of July 1835, page 503.

(It says: "A meeting took place on Wednesday evening at Battersea fields between R. J. Mackintosh Esq., attended by Major General Sir John Campbell and William Wallace, Esq. attended by Dr Richard Burke. The word having been given, Mr Mackintosh's pistol missed fire, and Mr Wallace fired in the air. A second fire took place without effect, and the parties, after a mutual explanation, shook hands.")

(It says: "A meeting took place on Wednesday evening at Battersea fields between R. J. Mackintosh Esq., attended by Major General Sir John Campbell and William Wallace, Esq. attended by Dr Richard Burke. The word having been given, Mr Mackintosh's pistol missed fire, and Mr Wallace fired in the air. A second fire took place without effect, and the parties, after a mutual explanation, shook hands.")

Labels:

1835,

burke,

C19,

campbell,

duel,

england,

family history,

mackintosh,

stories,

wallace

Summoned by loyalty, a soldier returns to the field, but for the wrong side

In 1824, Sir John Campbell found himself, at the age of 44, a widower with a 6-year-old daughter, and in mourning for his 3-year-old son. Before the year was out, he had resigned from the army, where he had distinguished himself in fighting in Portugal during the Peninsular Wars of the early 19th century. He and young Elizabeth were apparently living quietly in London. Then everything changed, again.

Sir John's late wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, was Portuguese and I suspect from a good family. Sir John himself was friends with the royal family, or at least, part of it. By the late 1820s, Portugal was in a crisis over succession, which was a fight between one brother (Dom Pedro) favouring a constitutional monarchy and reform, and the other (Dom Miguel) wanting to stay with an absolute monarchy. It turned into a civil war.

The story of the Portuguese War of the Two Brothers is complicated. The highlights, for my purposes are simple enough, though.

British soldiers fought on both sides! Their leaders were officers who had been brothers in arms in the earlier Peninsular Wars. Men on both sides held knighthoods in both England and Portugal. All of them were at least notionally fighting illegally, according to the Foreign Enlistment Act.

To make things a little awkward for me in the research department, there were too many Campbells around, officers with the KCTS decoration, who served in the Peninsular Wars and possibly in this Portuguese civil war. Anyone who decides to study the story more closely will need to be cautious. I can only hope I am not getting the facts too confused.

There is no doubt that Sir John Campbell of my story, the man who eventually lives at 51 Charles Street, was at the head of the Miguelite forces, as they were called. He supported the absolutist cause whole-heartedly. On the other side were Admiral Sartorius and then Sir Charles Napier. Their respective forces were a mixture of English and Portuguese, and not professional soldiers, but what we might charitably call a motley crew.

A few brief glances at some of the debates in the House of Lords and the Commons after the war ended indicates that the British politicians were not in unanimous support of either side in the Portuguese war. Again, this is an over-simplification, but Sir John became something of a political football.

In the early days of the war, his side did well, but then the tide turned. Sir John was captured on board a ship (apparently leaving Portugal) with some allegedly incriminating papers. Papers or no, his side had lost. He became a prisoner of war.

This was an unpleasant imprisonment. Reading between the lines, I suspect there was a good deal of seeking revenge involved, because in some quarters the Miguelites had a reputation for being barbaric to their own prisioners. English visitors to Portugal after the war, in the early 1830s, reported seeing Sir John behind the bars of the prison compound.

His appeals to the English government for help went unanswered, on the basis that he was fighting in a foreign war on foreign soil, not in a British cause.

Why did he do it?

I've read that Sir John was a personal friend of Dom Miguel from his earlier time in Portugal, and I assume that the granting of the honour of KCTS, whenever that was, cemented that friendship. Sir John's politics must have been conservative, which mattered a great deal against the backdrop of the Reform movement in England.

He was held for at least nine months, much of which was apparently in solitary confinement. The degree of deprivation is in the eye of the beholder, but certainly it was a hard time, during which he was abandoned by his country.

I'm a little surprised that he was ever allowed to return to England. Having fought for the losing side in a battle that put British soldiers against each other, he could have been called treasonous without a huge stretch of the imagination.

I suspect what saved him was the fact that no one had clean hands.

By the time he returned to England in about 1834, his daughter was 16. He had been away from her for a few years (at least).

Here was a man who had spent much of his life achieving honour and glory as a soldier, only to end up disgraced. In the Commons debates, reference was made to his having a Portuguese wife (with the implication being that his loyalty wasn't to Britain), but no one pointed out that Maria Brigida had been dead for ten years.

He'd lost his wife and son, had hardly seen his daughter, had fought on a losing side and been imprisoned, and could probably never return to the country he must have come to love, Portugal.

He had reason to be a bitter and disappointed man, and maybe he was. Or, maybe he was so convinced of the rightness of his cause that he spent the rest of his life deploring the wrongs done to him. I don't know. The dictionary of biography says he lived a quiet life.

The quiet lasted until 1863, some 20 years after the civil war ended. It was then succeeded by that quiet which comes to us all, one day.

The first book, by Shaw, is about the War of Two Brothers. The other two books are from the Duke of Wellington's earlier experiences in Portugal. I have written before that Sir John Campbell was mentioned favourably in dispatches by Wellesley, late the Duke, but this may not be true, or it may be true but some of the mentions may refer to other Campbells. I post links to some of the books here in case anyone is interested in finding out more.

Sir John's late wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, was Portuguese and I suspect from a good family. Sir John himself was friends with the royal family, or at least, part of it. By the late 1820s, Portugal was in a crisis over succession, which was a fight between one brother (Dom Pedro) favouring a constitutional monarchy and reform, and the other (Dom Miguel) wanting to stay with an absolute monarchy. It turned into a civil war.

British soldiers fought on both sides! Their leaders were officers who had been brothers in arms in the earlier Peninsular Wars. Men on both sides held knighthoods in both England and Portugal. All of them were at least notionally fighting illegally, according to the Foreign Enlistment Act.

To make things a little awkward for me in the research department, there were too many Campbells around, officers with the KCTS decoration, who served in the Peninsular Wars and possibly in this Portuguese civil war. Anyone who decides to study the story more closely will need to be cautious. I can only hope I am not getting the facts too confused.

There is no doubt that Sir John Campbell of my story, the man who eventually lives at 51 Charles Street, was at the head of the Miguelite forces, as they were called. He supported the absolutist cause whole-heartedly. On the other side were Admiral Sartorius and then Sir Charles Napier. Their respective forces were a mixture of English and Portuguese, and not professional soldiers, but what we might charitably call a motley crew.

A few brief glances at some of the debates in the House of Lords and the Commons after the war ended indicates that the British politicians were not in unanimous support of either side in the Portuguese war. Again, this is an over-simplification, but Sir John became something of a political football.

In the early days of the war, his side did well, but then the tide turned. Sir John was captured on board a ship (apparently leaving Portugal) with some allegedly incriminating papers. Papers or no, his side had lost. He became a prisoner of war.

This was an unpleasant imprisonment. Reading between the lines, I suspect there was a good deal of seeking revenge involved, because in some quarters the Miguelites had a reputation for being barbaric to their own prisioners. English visitors to Portugal after the war, in the early 1830s, reported seeing Sir John behind the bars of the prison compound.

His appeals to the English government for help went unanswered, on the basis that he was fighting in a foreign war on foreign soil, not in a British cause.

Why did he do it?

I've read that Sir John was a personal friend of Dom Miguel from his earlier time in Portugal, and I assume that the granting of the honour of KCTS, whenever that was, cemented that friendship. Sir John's politics must have been conservative, which mattered a great deal against the backdrop of the Reform movement in England.

He was held for at least nine months, much of which was apparently in solitary confinement. The degree of deprivation is in the eye of the beholder, but certainly it was a hard time, during which he was abandoned by his country.

I'm a little surprised that he was ever allowed to return to England. Having fought for the losing side in a battle that put British soldiers against each other, he could have been called treasonous without a huge stretch of the imagination.

I suspect what saved him was the fact that no one had clean hands.

By the time he returned to England in about 1834, his daughter was 16. He had been away from her for a few years (at least).

Here was a man who had spent much of his life achieving honour and glory as a soldier, only to end up disgraced. In the Commons debates, reference was made to his having a Portuguese wife (with the implication being that his loyalty wasn't to Britain), but no one pointed out that Maria Brigida had been dead for ten years.

He'd lost his wife and son, had hardly seen his daughter, had fought on a losing side and been imprisoned, and could probably never return to the country he must have come to love, Portugal.

He had reason to be a bitter and disappointed man, and maybe he was. Or, maybe he was so convinced of the rightness of his cause that he spent the rest of his life deploring the wrongs done to him. I don't know. The dictionary of biography says he lived a quiet life.

The quiet lasted until 1863, some 20 years after the civil war ended. It was then succeeded by that quiet which comes to us all, one day.

The first book, by Shaw, is about the War of Two Brothers. The other two books are from the Duke of Wellington's earlier experiences in Portugal. I have written before that Sir John Campbell was mentioned favourably in dispatches by Wellesley, late the Duke, but this may not be true, or it may be true but some of the mentions may refer to other Campbells. I post links to some of the books here in case anyone is interested in finding out more.

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

The young Portuguese bride of Sir John Campbell: Dona Maria Brigida

I have mentioned a few things about Sir John Campbell, KB, KCTS, and left off suggesting that the KCTS (Knight Commander of the Tower and the Sword, Portugal) shaped his life.

As far as I can tell, Sir John Campbell stayed in Portugal after the Peninsular Wars, on loan to the Portuguese army until 1820. He left when the constitutionalists started to become too heated. When he returned to England, he lived in Baker Street with his Portuguese wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, and Elizabeth, their daughter, who was born in Lisbon in 1818.

Sir John and Maria Brigida were married in 1816. She was 18 years old. He was 36.

Upon their return to England in 1820, or perhaps shortly before, their son, John David Campbell, was born. Elizabeth and John David are the only children I know of in this family.

Sir John was given what sounds like a reasonably quiet job in England, in command of the 75th Regiment of Foot while they were at home and not off fighting abroad. This is a famous regiment (the Gordon Highlanders) but during Sir John's tenure, I have the impression nothing much happened. (Another avenue for the eager military historian to pursue.)

I wish I could draw the curtain here and say they lived happily ever after. At this point, Portugal was experiencing unrest but not war, and Sir John had a comfortable family life in London, from the sounds of it.

Alas.

Some day I would like to go to the Parish Church in Marylebone.

View Larger Map

I've seen it from the outside without knowing (nor, at that time, caring) but haven't gone in.

As far as I can tell, there is still a plaque on the east wall, reading as follows.

Having lost his wife and little boy between 1821 and 1824, Sir John retired from the army and sold his commission by the 1st of October, 1824. Thus he and young Elizabeth (only 6 years old when her brother died; motherless since age 3) were apparently left alone.

There is always the possibility that Sir John married a second time during this period. I have found no mention of such an event, however, and the notes in biographic sources are consistent in saying he had two wives.

At this point my impression of Sir John is that he was living quietly and was enjoying a life of reasonably high social standing. His sisters and brothers appeared to have married well, and he probably had good family connections on his mother's side (the Pitcairns). I would say the same of his father's, but I haven't been able to trace them back with any confidence.

Things were about to change, and the KCTS was going to make a big difference in Sir John's life.

As far as I can tell, Sir John Campbell stayed in Portugal after the Peninsular Wars, on loan to the Portuguese army until 1820. He left when the constitutionalists started to become too heated. When he returned to England, he lived in Baker Street with his Portuguese wife, Dona Maria Brigida do Faria e Lacerda, and Elizabeth, their daughter, who was born in Lisbon in 1818.

Sir John and Maria Brigida were married in 1816. She was 18 years old. He was 36.

Upon their return to England in 1820, or perhaps shortly before, their son, John David Campbell, was born. Elizabeth and John David are the only children I know of in this family.

Sir John was given what sounds like a reasonably quiet job in England, in command of the 75th Regiment of Foot while they were at home and not off fighting abroad. This is a famous regiment (the Gordon Highlanders) but during Sir John's tenure, I have the impression nothing much happened. (Another avenue for the eager military historian to pursue.)

I wish I could draw the curtain here and say they lived happily ever after. At this point, Portugal was experiencing unrest but not war, and Sir John had a comfortable family life in London, from the sounds of it.

Alas.

Some day I would like to go to the Parish Church in Marylebone.

View Larger Map

I've seen it from the outside without knowing (nor, at that time, caring) but haven't gone in.

As far as I can tell, there is still a plaque on the east wall, reading as follows.

"To the memory of

Dona Maria Brigida do Faria

E Lacerda

Wife of

Sir John Cambell, K.C.T.S.

Lieut Col in the British, and Maj Gen in the Portuguese Service.

She died much lamented

on the 22nd Jan 1821, in the 24th Year of her age;

Her remains are deposited in a vault of this Church.

Also of

John David Campbell

Son of the above who died 28 May 1824

Aged 3 years and 9 months"

http://www.archive.org/stream/miscellaneagene01howagoog#page/n31/mod e/2up

Having lost his wife and little boy between 1821 and 1824, Sir John retired from the army and sold his commission by the 1st of October, 1824. Thus he and young Elizabeth (only 6 years old when her brother died; motherless since age 3) were apparently left alone.

There is always the possibility that Sir John married a second time during this period. I have found no mention of such an event, however, and the notes in biographic sources are consistent in saying he had two wives.

At this point my impression of Sir John is that he was living quietly and was enjoying a life of reasonably high social standing. His sisters and brothers appeared to have married well, and he probably had good family connections on his mother's side (the Pitcairns). I would say the same of his father's, but I haven't been able to trace them back with any confidence.

Things were about to change, and the KCTS was going to make a big difference in Sir John's life.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)